Captioning Is Not a Footnote

A review of the 1999 film Compensation

I don’t know much of anything about captioning. And I feel a creeping sense of dread every time I’m prompted to write alt text for an image. It’s not that I don’t care, but I worry about getting it wrong, about failing to describe a thing with the fullness it deserves. How does one describe an image in a way that’s both accurate and not overly subjective? How do you not flatten the thing being shared? Clearly, I’m overthinking.

None of this, at first glance, has much to do with the film I watched this evening, Compensation, directed by Zeinabu irene Davis. But, as it turns out, the captioning throughout the film was my favorite part. Did you know the sound sheep make is called bleating? I learned that a few hours ago via a caption. It struck me not because I didn’t know sheep made noise, but because I’d never needed to name it, or I named the sound.

I learned American Sign Language as a child. Not fluently, my vocabulary stalled out somewhere in middle school. But four years ago, I picked it back up with intention. I had a neighbor I wanted to communicate with. Since then, I’ve moved to Michigan, and I haven’t had a language partner to practice with. Fluency is still, for me, more aspiration than reality. Yet, I’ve learned enough to feel that world-altering shift that comes with learning a second language, language isn’t words, but a new way of being in the world.

With ASL, that shift is uniquely visceral. New learners often assume, wrongly, that there’s a direct one-to-one translation between English and ASL. That there’s a sign for every English word. But American Sign Language is not English signed. It is its own language, with its own grammar and syntax. Most importantly, it’s rooted in a culture that doesn’t treat deafness as a lack. Deaf culture resists the framing of deafness as disability; an idea I’m drawn to as a disabled person.

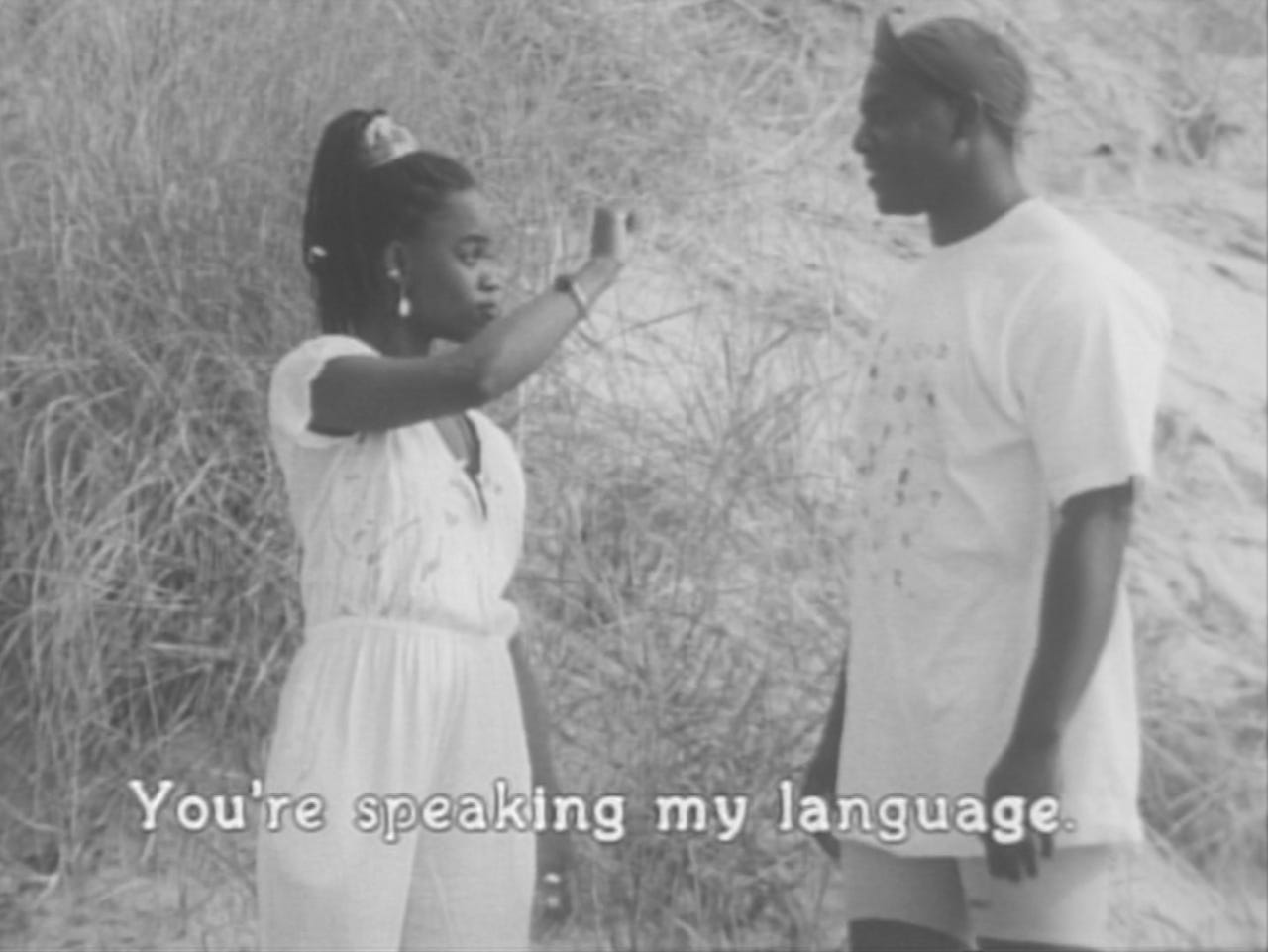

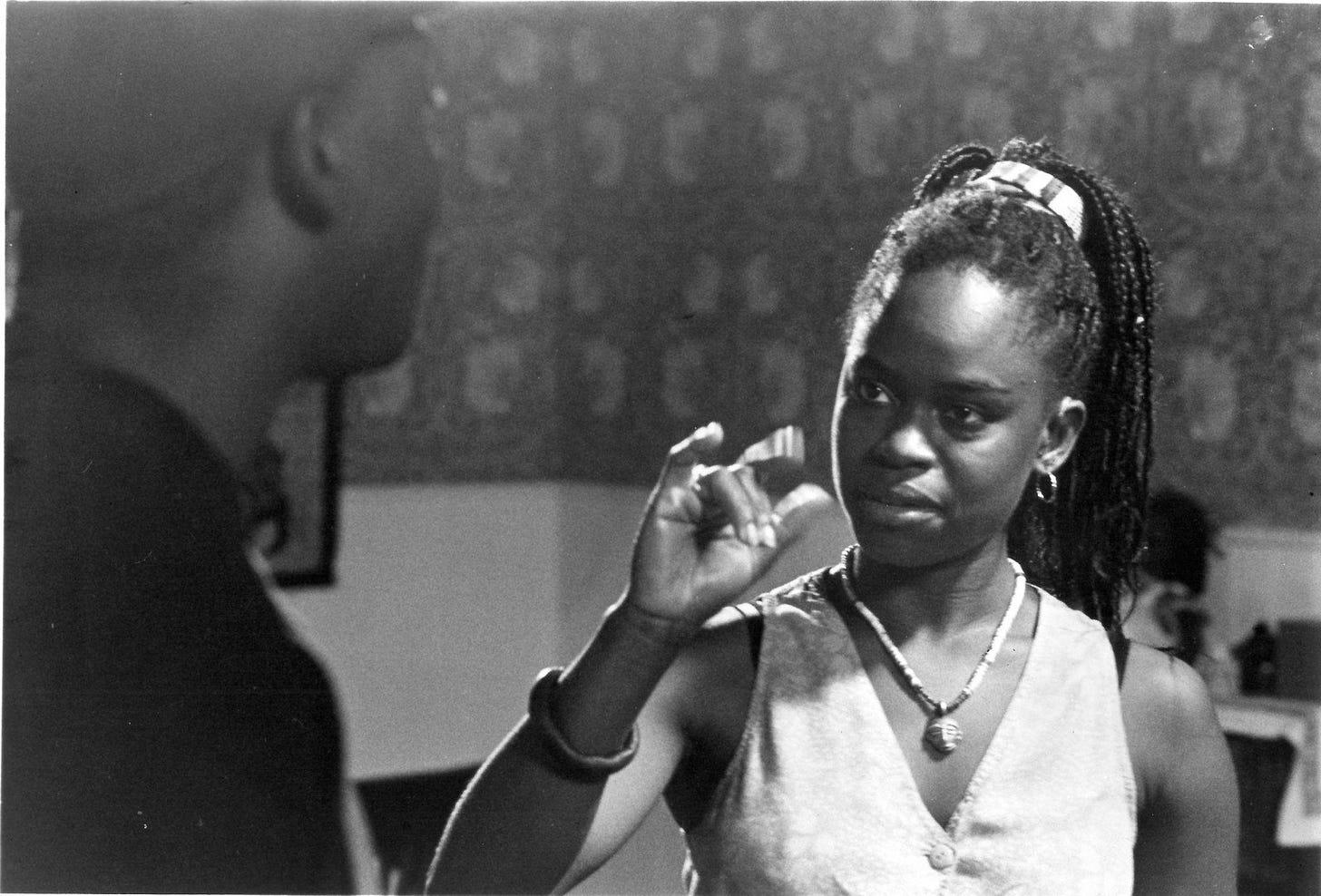

Compensation is a quiet film with a radical structure. Zeinabu irene Davis tells two love stories across parallel timelines: one set in early 20th-century Chicago, and one in the contemporary city. Each follows a Deaf woman and a hearing man, lovers navigating intimacy, and the shifting landscapes of race, ability, and language. The same two actors (Michelle A. Banks and John Earl Jelks) play both couples, moving across time. The effect is striking, not because the stories are identical, but because they rhyme. In love, difference is not transcended but explored and lived with through communication and commitment.

Davis constructs the film with the sensibility of a poet and the discipline of a historian. The silent film tradition is folded into the first narrative, echoing the aesthetics of early Black cinema. Intertitles are used, not just to convey dialogue but to slow the viewer down, to force reflection on language itself. The present-day story, by contrast, uses synchronized sound but keeps ASL at its center. The result is a film that doesn't simply include Deafness, it structurally prioritizes Deaf ways of knowing. Dialogue is not merely heard or spoken; it is signed, translated, captioned, embodied.

Accessibility is also a major theme, not just as a legal or ethical checkbox, but as an aesthetic choice. Captions are not hidden. They are integrated, stylized, and expressive. They describe not only speech, but sound: music, city noise, footsteps, the bleating of sheep. This attention to captioning changes the experience of watching. It reminds the hearing viewer that sound is not neutral.

Compensation does not assume its audience. It does not over explain. And, it’s not a perfect film, some narrative transitions are abrupt, and the dual timeline can occasionally feel uneven. But these are formal tensions that reflect the complexity of its subject matter. This is a film about layered identities: Blackness, Deafness, queerness- and with a historical memory, and it refuses to flatten them.

If you live in Detroit, you can see Compensation for it’s final day at the DFT tomorrow. Buy tickets here.